Cappadocia and Catalhöyük

The world is full of mysteries and wonders from ages that have faded into the mists of once upon a time. Remnants of those times dot the planet, decorate cave walls, and sit silently under the depths of the sea. Occasionally, if we ask the right questions, and really look, we can lift the veil of mystery a bit and catch a glimpse of the cultures that created such resilient structures and images. Duncan-Enzmann has done that here, shedding light on two seemingly unrelated mysteries. And with what we learn about them, we can look with different eyes at many other vestiges of ancient peoples.

Catalhöyük

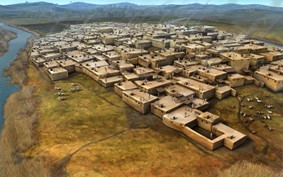

Catalhöyük was a Neolithic settlement in southern Anatolia (“land where the sun rises”), modern-day Turkey. It existed from ca. 7500 to 5700 BC. The settlement rises sixty-five feet above the surrounding plain. It is the largest and best-preserved Neolithic site found to date. Cappadocia’s underground cities were built thousands of years later, around 1000 BC, under the ground in eastern Anatolia. One of these cities was large enough to shelter 20,000 people.

These two ancient places share a mystery, yet Catalhöyük is built like a honeycomb, all connected, with entrances on the rooftops, and Cappadocia’s underground cities span miles, connected by tunnels. They look as different as two cities can look. They do not even occupy the same strata of earth. So what is it that these two places share?

The people who built Catalhöyük and Cappadocia had an impressive understanding of caves. This is knowledge they inherited from millennia before, passed on to them from people who learned about caves at Lascaux, ca. 16,000 BC. This is what links these two ancient wonders together. The people who built them both had to know about caves. This leads us to a couple of questions.

The first question is: If you were standing at the mouth of a cave in the winter, which way would the air be flowing? It would flow out of the cave; caves are underground where it is warm, and warm air rises, so it would flow out of the cave through the opening on the surface.

It is curious how the houses at Catalhöyük are built – connected, with rooftop entrances. Why would they build them like that? The city was a fortress, the manner of construction made it easier to protect the homes. But that is not the only reason. Honeycombing them together, and sharing walls is efficient for heat. Ventilation is facilitated even in the inner houses by rooftop doors. We have a huge fan in the top floor ceiling of our house to exhaust the heat that collects there. Just as it does in caves, the air flows up and out.

The second question is: What happens to soft volcanic ash when it is exposed to air? It solidifies into very hard rock. This is why the wondrous cities under the ground at Cappadocia could be built – if built is the right word. Inquiries as to why build them this way are raised here as well. It must have been more work than building shelters above ground would have been.

Duncan-Enzmann’s historical timeline shows us that for millennia the proto-European culture watched the skies, notating their observations with symbols we still use today. They created planter’s calendars to predict the seasons and allow horticulture to thrive. Every advancement in their observations improved the calendar and improved the lives of all the people. They knew when winter was coming and could prepare not only food stores but clothing and shelter as well. What may surprise you is that they also knew when the next ice age was coming. Today, the Milankovitch cycles explain when and why our world freezes and thaws. Our ancestors also knew about these cycles, and they constructed underground cities to survive the iron-cold temperatures, which could be fifty to 80 below zero for months, plus wind chill factor. It is warmer under the earth.

Another clever engineering feat at Cappadocia is the tubes that run from the surface through six to as much as forty feet of rock into the underground dwellings. They are small round tubes about 4” in diameter. Here we must go back to the cave in winter, and picture the heat rising out of the mouth. The entrances to the underground cities are large, and the air flows easily. As it flows out, more must come in from somewhere. The tubes in the rock allow fresh air from the surface to flow into the dwellings. But – isn’t it cold up there? It was, but rocks are warm underground. So as the air flows through the tubes it is heated by the rock. The culture that lived in these homes had fresh, warm air all winter.

Our planet is covered with mysterious structures. Theories abound as to their origin and purpose; perhaps with the information Duncan-Enzmann has contributed, we can look more carefully at them and see what actually could have been. Our ancestors were very, very clever; they survived the ice ages. Could you?